Professional Practice Standards 2023

Version 6

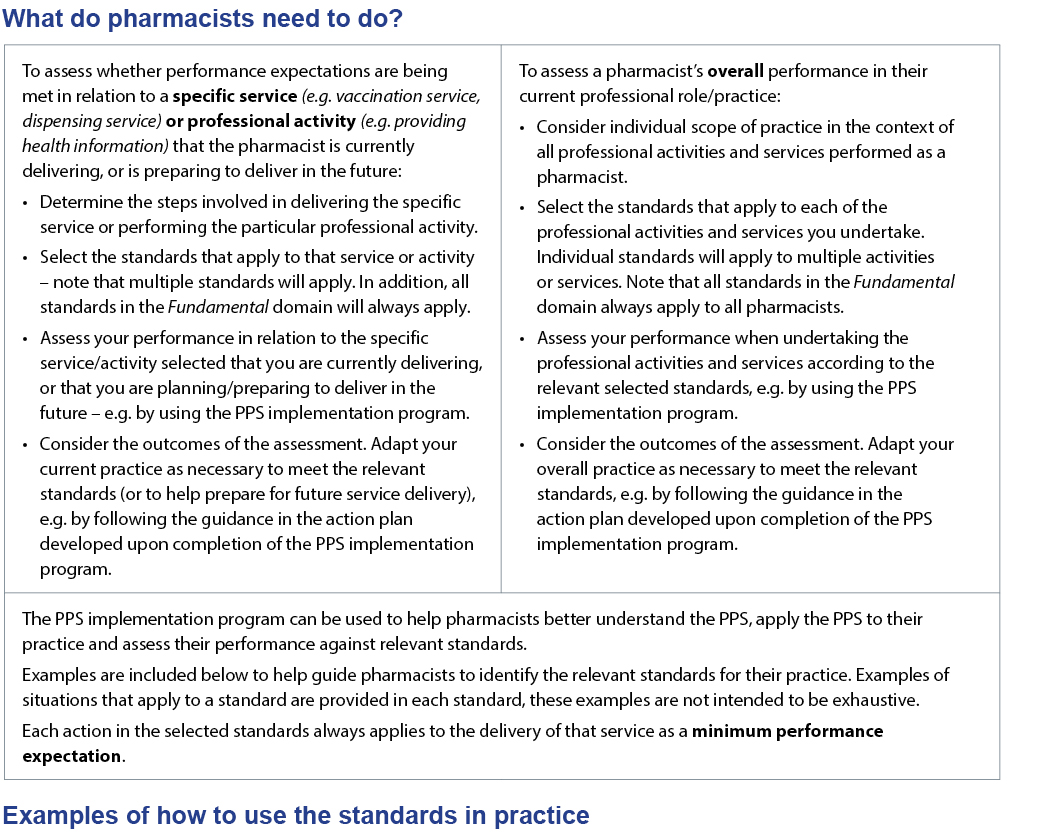

Pharmacists have a fundamental responsibility to ensure safe and effective delivery of healthcare services. The Professional Practice Standards (PPS) are used to assess whether a pharmacist’s performance enables delivery of safe, high-quality, reliable and clinically effective healthcare services. Practising according to accepted standards supports medicine safety and quality use of medicines.

The PPS apply to the practice of all pharmacists, regardless of their professional role or the scope, level or location of their practice.

The Pharmacy Board of Australia (the Board) defines ‘practice’ (adapted) as follows:

To practise as a pharmacist means undertaking any role, whether remunerated or not, in which the individual uses their skills and knowledge as a pharmacist in their profession. Practice is not restricted to the provision of direct clinical care. It also includes working in a direct nonclinical relationship with individuals and others; working in management, administration, education, research, advisory, regulatory or policy development roles, and any other roles that impact on safe, effective delivery of services in the profession.

The Professional Practice Standards:

The Professional Practice Standards self-assessment and quality improvement program can help you better understand and implement the standards into your practice. You will be guided through how to select the standards applicable to your overall practice or a specific service, complete self-assessment against each of the actions, listen to pharmacists discuss the importance of the standards and be provided with a tailored action plan to help you improve your practice. Successful completion of the program will allow you to record Group 2 CPD credits and working through the guidance in the Action plan can enable you to self-record Group 3 CPD credits.

Discussion of how the Professional Practice Standards are used to ensure pharmacist practice enables delivery of safe, high-quality, reliable and clinically effective healthcare services.

Pharmacists continue to play a crucial role in ensuring safe and reliable access to medicines and healthcare services, particularly during public health emergencies such as floods, fires, and the pandemics. As the scope of pharmacist practice continues to expand, it is critical that pharmacists have an up-to-date and evidence-based foundation to guide their professional practice. A key component of the support needed is clear and actionable Professional Practice Standards.

Triggered by policy changes (e.g. expansion of pharmacistadministered vaccination services), changes in practice, emerging research on the utility of guidance documents and the scheduled review cycle, an update of Version 5 of the Professional Practice Standards was considered timely and essential.

The review process involved input from many individuals and organisations, including pharmacists practising in different settings and career stages, consumer representatives, regulators, educators, researchers and government agencies. The result is a contemporary and evidence-based resource that provides improved clarity and usability for pharmacists across different roles, practice settings and career stages.

We extend our heartfelt thanks to all those involved in the significant body of work to review, revise and update the Professional Practice Standards. The level of work and cooperation observed is a testament to a profession that is clearly committed to striving for quality practice that improves the health of Australians.

We encourage all pharmacists to use the newly revised and updated Professional Practice Standards as a contemporary, evidence-based resource to guide their quality professional practice. By incorporating these standards into daily practice, pharmacists will ensure safe, effective and person-centred care for all Australians.

Dr Deanna Mill

Chair

Project Advisory Group

July 2023

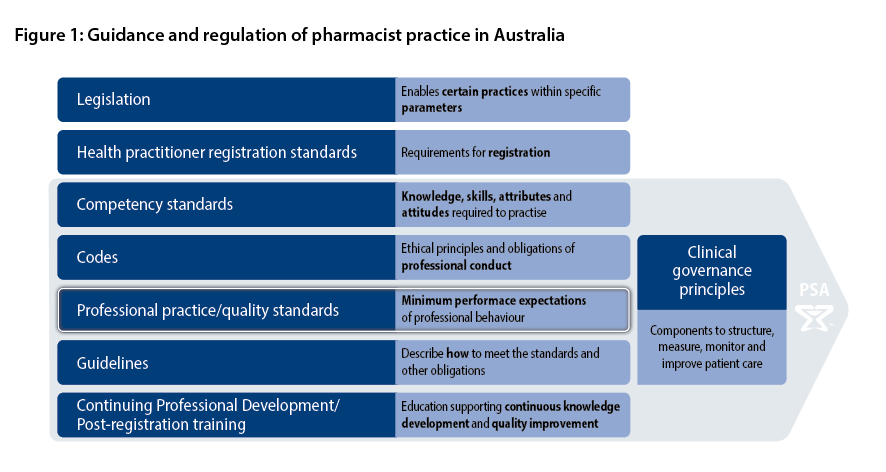

The overall framework underpinning the practice of pharmacists consists of several groups and layers of interdependent policies, legislation, and professional and ethical resources. The relationship between documents that articulate, govern and guide pharmacist practice is shown in Figure 1.

Pharmacists must use the PPS in conjunction with, and always comply with, relevant legislation, regulatory frameworks, other standards and codes of ethics, conduct and practice. Pharmacists must also be informed by organisational policies and procedures, and professional practice and treatment guidelines.

The national competency standards and the PPS are complementary to each other. The national competency standards describe the skills, attitudes and other attributes (including values and beliefs) attained by an individual based on knowledge (gained through study) and experience (gained through subsequent practice) that together enable the individual to practise effectively as a pharmacist. The PPS define and articulate the minimum expected standards of professional behaviour by pharmacists in Australia. Pharmacists are expected to be competent when applying the PPS to their practice. Both the competency standards and the PPS must be met to ensure the delivery of high-quality services by pharmacists.

Details of legislative requirements are beyond the scope of the PPS. However, when required, PSA will provide guidance to pharmacists on new or amended requirements, clarify professional obligations and assist with interpretation guidance or legislative documents.

At all times, pharmacists must comply with relevant Commonwealth and state or territory legislation. No part of the PPS should be interpreted as permitting a breach of the law or discouraging compliance with legal requirements.

Relevant organisations

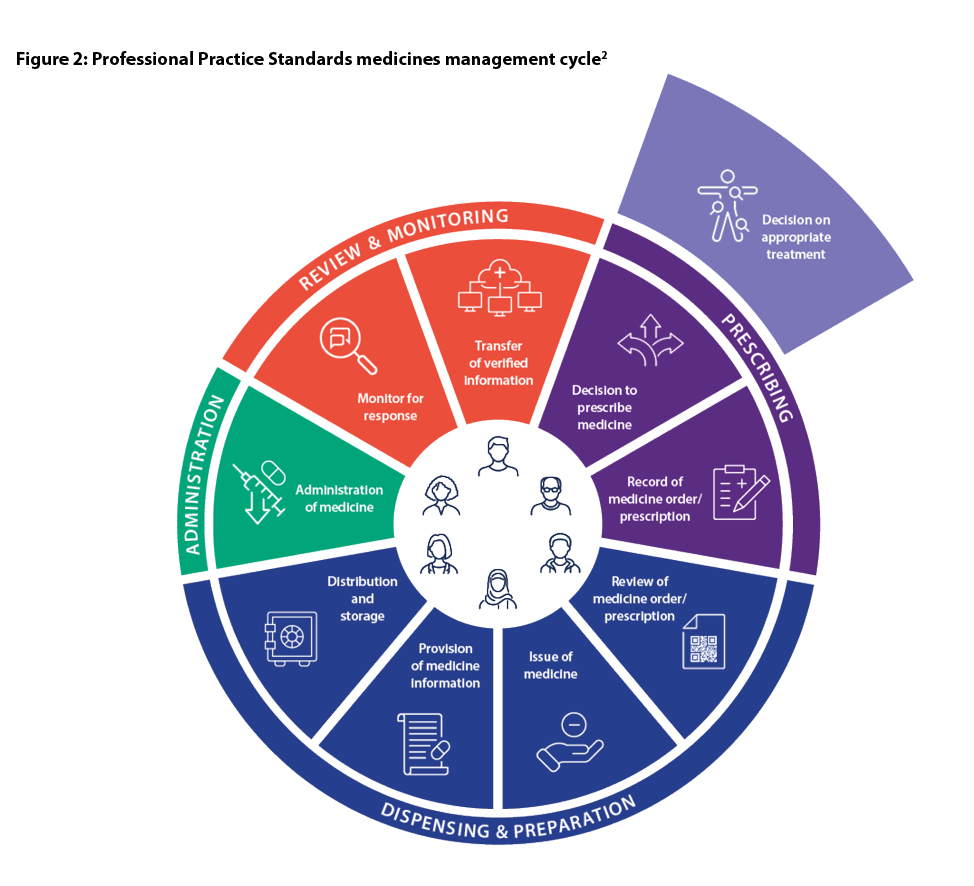

Relevant organisationsThe PPS have been designed to reflect the dynamic healthcare environment pharmacists work within. The safe and effective use of medicines is at the core of pharmacy practice. Pharmacists’ roles have evolved significantly and pharmacists practise at all phases of the medicines management cycle (MMC).

To demonstrate this evolution, the PPS have been redesigned to reflect the alignment with the MMC.

Pharmacists practise in all steps of the medicines management cycle.

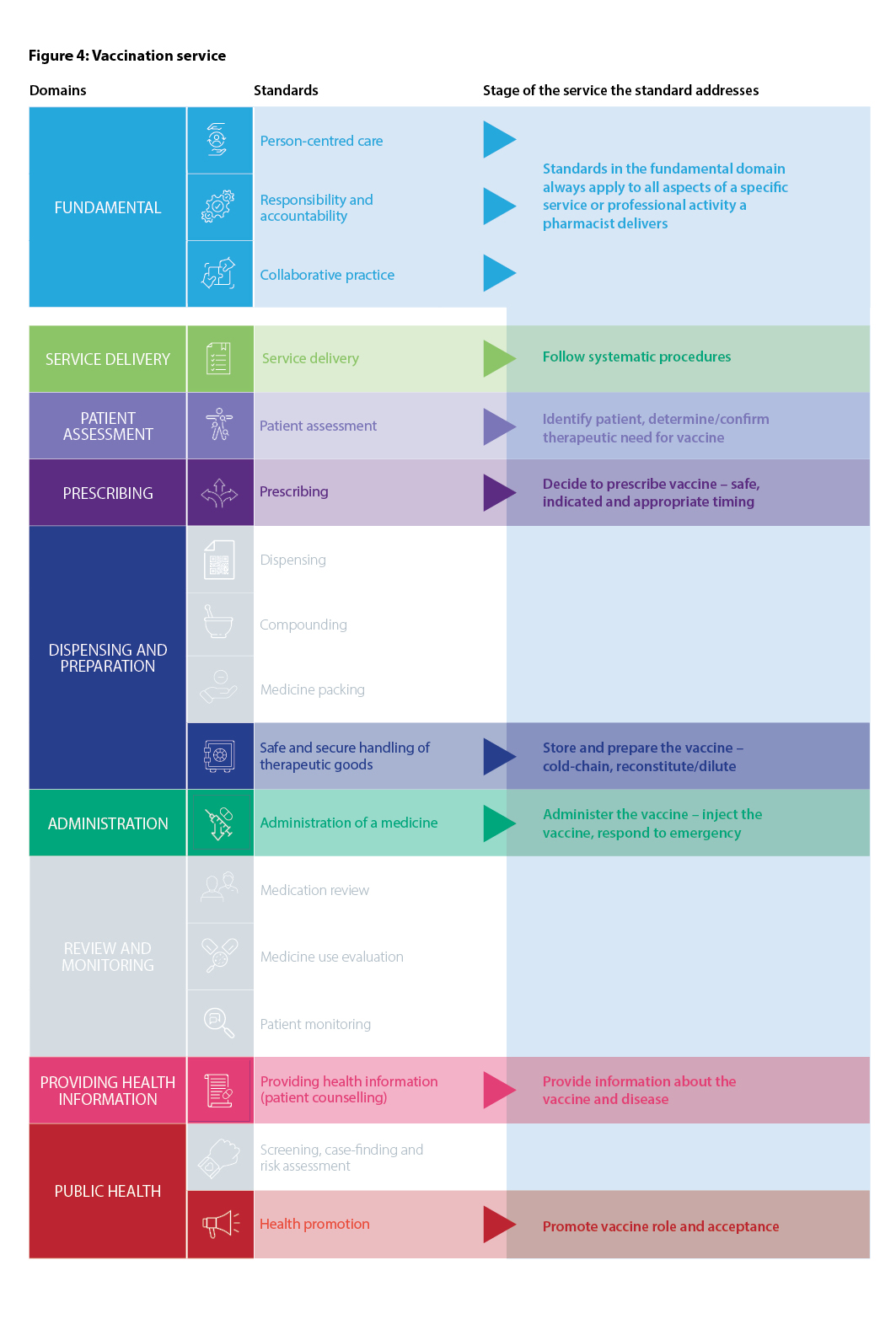

Recognising the variety of roles pharmacists have in health care, including roles not directly involved in patient care, the Fundamental domain contains standards that are always relevant to all registered pharmacists, regardless of practice setting. These standards should always be used in conjunction with other relevant standards that apply to the delivery of a particular service or activity. The Fundamental standards are Person-centred care, Responsibility and accountability and Collaborative practice.

There are nine domains of the PPS. These are:

Figure 2, the PPS MMC, displays those domains relevant to the MMC.

Pharmacists need to be aware of all of the standards in the PPS to be able to determine the specific standards that apply to their practice. Figure 3, Domains and standards in the PPS, displays all of the standards aligned with the relevant domain.

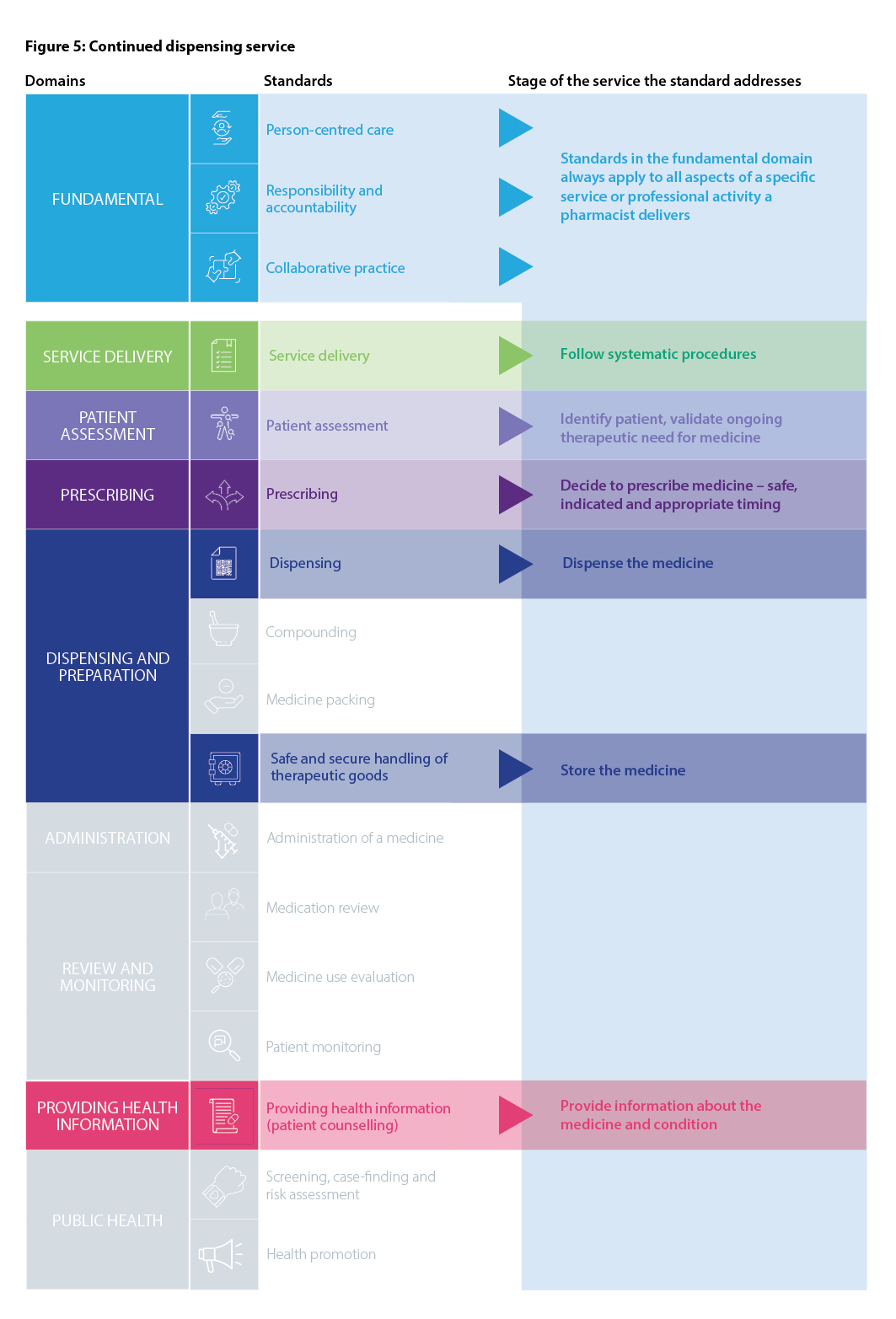

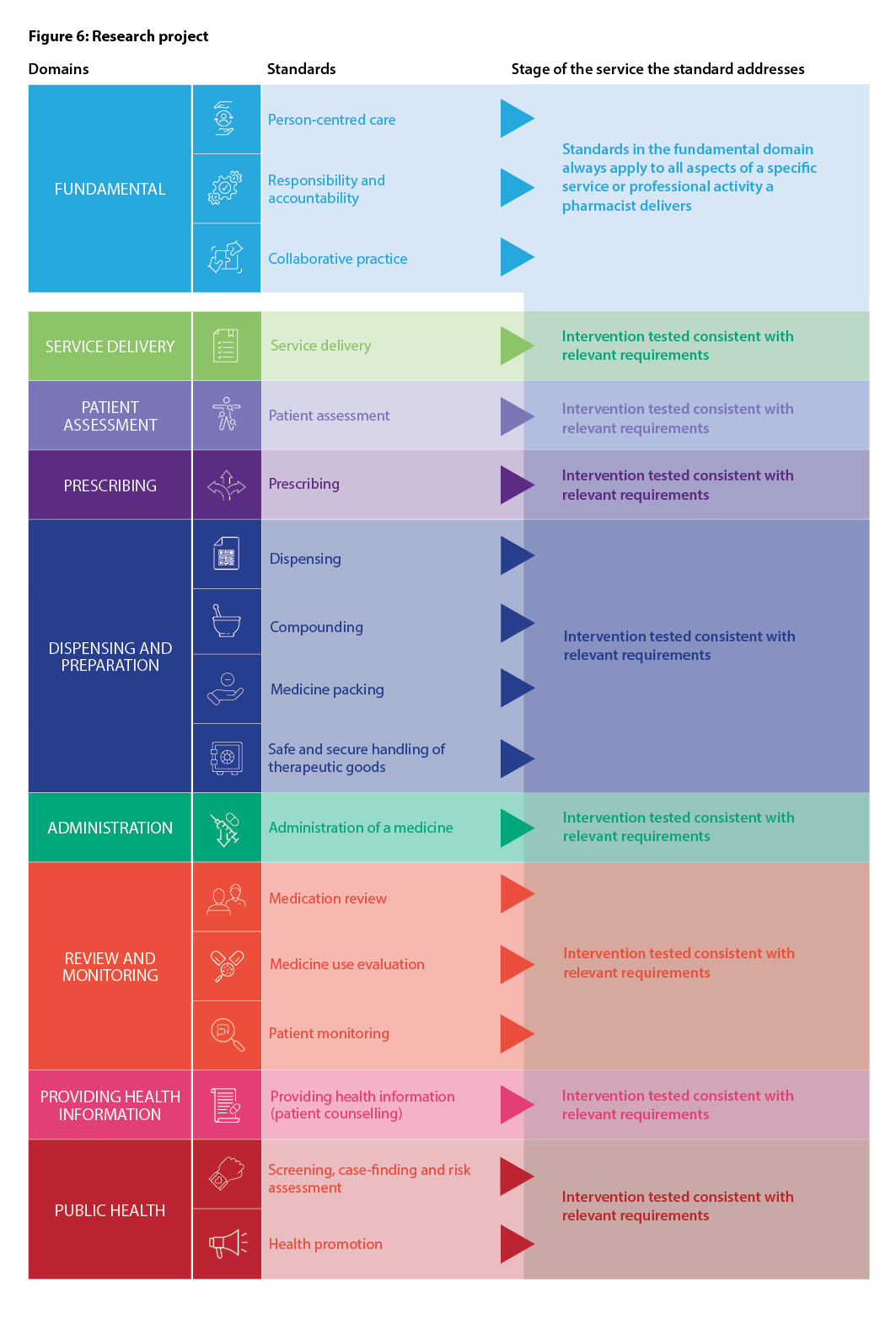

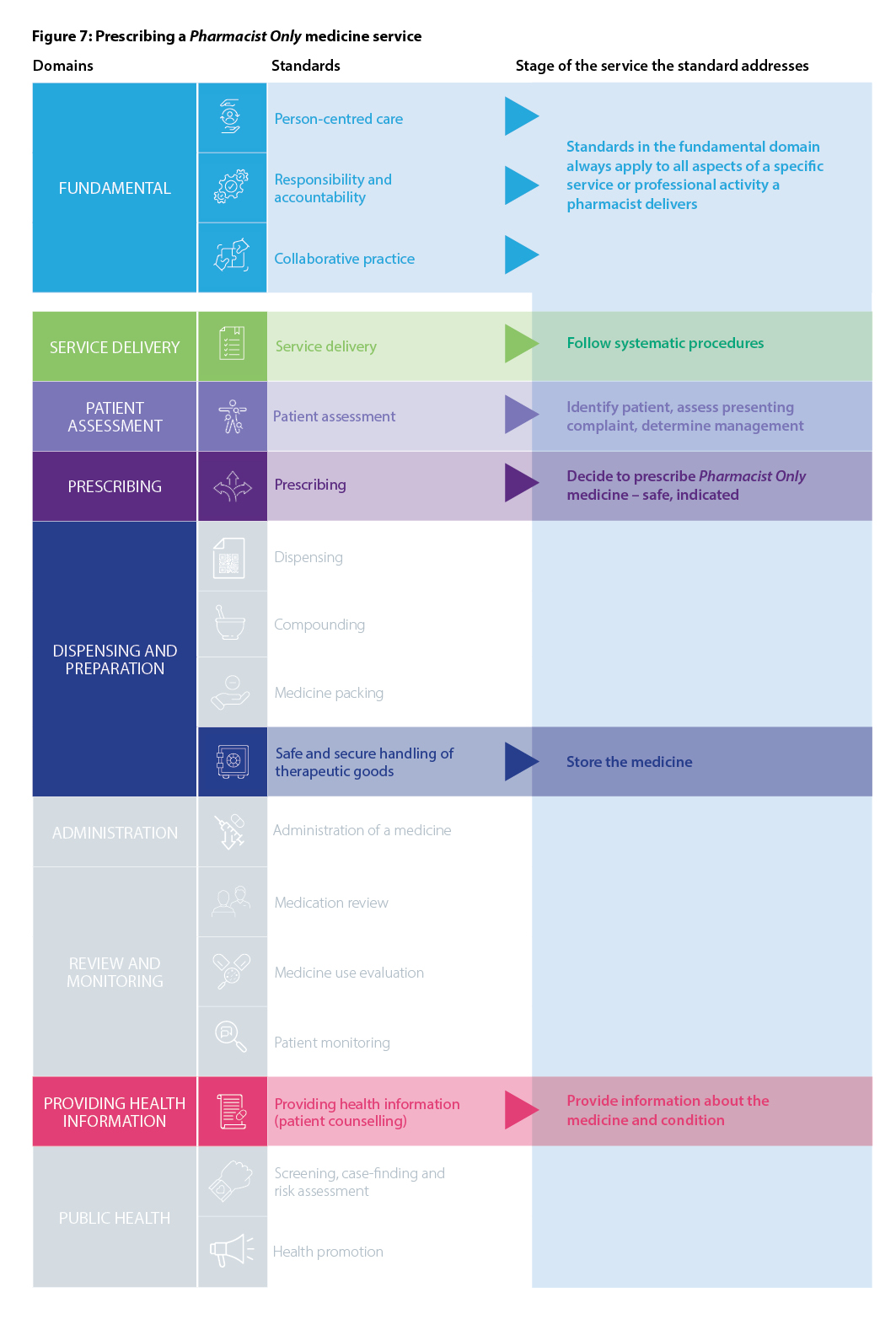

The pharmacist’s individual scope of practice will inform which standards apply. Pharmacists should consider the phases of the MMC that relate to each service or activity to be provided and apply the corresponding standards when providing the service or activity.

This standard is a fundamental standard to professional pharmacy practice.

It always applies to all registered pharmacists, regardless of the practice setting.

1. The pharmacist provides equitable, culturally safe, respectful and responsive health care to all people.

2. The pharmacist supports the person to actively participate in and make informed decisions about their health care through shared decision-making (e.g. uses management plans, considers health literacy, discusses potential benefits and harms of treatment).

3. The pharmacist maintains the person’s privacy and confidentiality (e.g. information security). If this is breached, the pharmacist informs the patient and relevant regulatory bodies of the breach and circumstances as soon as is practical.

4. The pharmacist communicates effectively with the person (i.e. tailors the communication method to the needs of the person (e.g. cultural considerations, hearing, sight, literacy, cognition, language) and confirms the person’s understanding (e.g. teach-back technique)).

5. The pharmacist provides current, relevant and evidence-based advice to the person (i.e. critically appraises the evidence).

6. The pharmacist works effectively and respectfully (e.g. communicates, collaborates) with the person and other members of the healthcare team to optimise the delivery of care to the person (e.g. referral, interdisciplinary team-based care, information sharing, developing and contributing to management plans).

This standard is a fundamental standard to professional pharmacy practice.

It always applies to all registered pharmacists, regardless of the practice setting.

Pharmacists are valuable contributors and can be leaders within the interdisciplinary team. The level of leadership will vary depending on the pharmacist’s role. Leadership obligations and, therefore, accountability for the service are increased when in senior clinical, managerial or organisational oversight roles (e.g. community pharmacy owner, chief pharmacist, director of clinical services, pharmacist manager, chief research investigator, sole operator, quality improvement manager, clinic manager, outreach manager).

Defining responsibility and accountability in the provision of health care is necessary for effective clinical governance.

1. The pharmacist actively supports and encourages team members to use and improve their knowledge and skills (e.g. provide appropriate training).

2. The pharmacist adopts principles of co-design and co-development when developing, designing or providing a service.

3. The pharmacist works with patients, communities, and other members of the healthcare team to identify areas of importance for health (e.g. low vaccine uptake, poor adherence to medicines, local outbreak of infectious disease).

4. The pharmacist designs and implements strategies to improve patient and community health (e.g. expansion of an immunisation service, implementation of a dose administration aid service, provision of education to colleagues and the public on infectious diseases).

5. The pharmacist reviews feedback received from patients or other members of the healthcare team to inform additional learning and training (e.g. continuing professional development).

6. The pharmacist self-assesses their knowledge, skills and attitudes to maintain professional competence and inform additional learning and training (e.g. continuing professional development).

7. The pharmacist demonstrates accountability (e.g. works transparently to clear objectives, accepts assessment of their performance), and accepts responsibility for their own actions and decisions and those of the team members they manage or oversee.

This standard is a fundamental standard to professional pharmacy practice.

It always applies to all registered pharmacists, regardless of the practice setting.

1. The pharmacist contributes to an open discussion about scope of practice, role and skills with other members of the healthcare team.

2. The pharmacist develops and maintains effective relationships with other members of the healthcare team.

3. The pharmacist works with other members of the healthcare team to coordinate the delivery of care to meet the patient’s goals, needs and preferences (e.g. referral, transitions of care, information sharing, contributing to management plans and healthcare records, negotiating overlaps in roles and tasks).

4. The pharmacist works collaboratively with other members of the healthcare team to develop, implement and monitor activities and services aimed at optimising the quality use of medicines and patient outcomes (e.g. medication use evaluations, medication reviews, research, health promotion activities).

5. The pharmacist communicates effectively with other members of the healthcare team to facilitate change (e.g. tailored communication, maintaining communication skills, frequent communication).

6. The pharmacist contributes to a culture of open communication and a receptive willingness to cooperate and communicate with other members of the healthcare team.

7. The pharmacist works collaboratively with other members of the healthcare team to identify areas to provide education to other healthcare team members (e.g. medicine information, therapeutic drug monitoring requirements, deprescribing).

8. The pharmacist adopts principles of co-design and co-development when providing education to other members of the healthcare team.

9. The pharmacist works collaboratively with other members of the healthcare team to contribute to the development of resources.

This standard always applies to all registered pharmacists providing services to patients.

It contains actions that apply to the delivery of any professional service.

Pharmacists in senior clinical, managerial or organisational oversight roles have an increased obligation to plan, resource, monitor and review services provided by the organisation (e.g. community pharmacy owner, chief pharmacist, director of clinical services, pharmacist manager, sole operator, quality improvement manager, clinic manager, outreach manager).

This standard describes universal quality systems needed to support and monitor clinical effectiveness and patient safety in any health service. These systems also define the scope of the service. The integration of these systems with requirements of other standards, both in this document and elsewhere support clinical governance by aligning to evidence for the service and accepted scope.

1. The pharmacist collaboratively develops a standard operating procedure for the service, prior to the implementation of the service, which:

2. The pharmacist follows and maintains the standard operating procedure for service delivery.

3. The pharmacist accepts responsibility for the safety, quality, efficiency and review of service delivery, including

third-party delivery.

4. The pharmacist confirms that delivery of the service will be in accordance with legislative, organisational and

professional requirements (e.g. professional indemnity insurance, workplace insurance, ethics approval).

5. The pharmacist confirms all contributors to the service (including third-party) are capable of delivering the service before providing the service (e.g. up-to-date knowledge and training, necessary skills, cultural safety training).

6. The pharmacist confirms all contributors to the service (including third-party) are appropriately qualified before providing the service (e.g. successful completion of required training, certifications, contractual guarantee).

7. The pharmacist provides appropriate facilities for the safe delivery of the service. If facilities are not appropriate, changes are made to correct this or the service is not provided. These facilities should include:

8. The pharmacist cleans the service delivery area using an evidence-based process according to the requirements of the service that minimises the risk of contamination (e.g. before and after each compounding activity or the administration of a medicine).

9. The pharmacist confirms there are sufficient contributors to the service to enable safe service delivery, including an emergency response, before providing the service (e.g. a suitable number of team members to complete all requirements of the service and respond to any potential emergency, contributors have capacity). If contributors are not sufficient, changes are made to correct this or the service is not provided.

10. The pharmacist creates and maintains a safe, non-judgemental service environment that allows those involved in delivering and receiving the service to communicate freely and openly.

11. The pharmacist assesses the possible impact to the environment and the wider community for delivery of the service. Where the impact is negative and can be reduced, the pharmacist implements the appropriate measures.

12. The pharmacist obtains informed consent from the patient before providing the service. This can include financial consent (e.g. costs to the patient), consent to access medical records or receive medicines, and consent to communicate with relevant persons involved in their care.

13. The pharmacist makes appropriate clinical decisions and recommendations (e.g. evidence-based, culturally appropriate) consistent with the patient’s management plan and relevant professional practice and treatment guidelines.

14. The pharmacist uses a suitable system (e.g. computer software, eHealth record, paper-based filing) to securely record, store, maintain, transmit and retrieve relevant patient details in the medication profile and healthcare record (e.g. electronic healthcare record) in accordance with legislative, organisational and professional requirements.

15. The pharmacist uses a suitable system to document a near miss or an incident after each occurrence (e.g. dispensing software, incident register).

16. The pharmacist uses a suitable system to report an incident after each occurrence in accordance with legislative, organisational and professional requirements (e.g. adverse reaction to a medicine to the Therapeutic Goods Administration, dispensing error to management and professional indemnity insurer).

17. The pharmacist seeks feedback on the service from patients, those involved in delivering the service and other stakeholders (e.g. evaluation and satisfaction surveys).

18. The pharmacist monitors and reviews feedback when received and implements changes to the service, when appropriate, as part of a quality improvement activity.

19. The pharmacist appropriately reviews all aspects of the service as part of a quality improvement and team training activity (e.g. conducts a review after feedback or when an incident occurs, reviews the accuracy of dose administration aid packing every month).

This standard always applies to registered pharmacists when assessing the person’s needs and determining appropriate management with them.

Examples of situations requiring patient assessment include:

1. The pharmacist confirms the person’s identity in accordance with legislative, organisational and professional requirements (e.g. using at least three approved identifiers).

2. The pharmacist establishes the person’s needs. This may include:

3. The pharmacist assesses the information gathered to:

4. The pharmacist discusses the findings with the person.

5. The pharmacist agrees on the most appropriate management with the person. This may include:

6. The pharmacist refers the person to the relevant healthcare professional if:

This standard always applies to registered pharmacists who are authorised to prescribe medicines and medical devices and are permitted to do so by legislation, requirements of the Pharmacy Board of Australia and policies of the state or territory, health service or employer for where they are located or employed.

Examples of prescribing include:

1. The pharmacist agrees on a management plan, including a medicine management plan, with the patient and relevant healthcare professional in accordance with legislative, organisational and professional requirements.

2. The pharmacist addresses any concerns and expectations raised by the patient after the management plan has been agreed (e.g. regarding their health, the management plan, the medicine management plan).

3. The pharmacist refers the patient to the relevant healthcare professional when the patient’s concerns, expectations or management are outside the pharmacist’s personal competence or scope of practice.

4. The pharmacist facilitates patient access to the therapeutic good in accordance with legislative, organisational and professional requirements (e.g. charting a medicine order, providing a Pharmacist Only or Prescription Only medicine to the patient).

5. The pharmacist shares the management plan with relevant healthcare professionals involved in the care of the patient (e.g. shares a record via secure messaging with other members of the healthcare team).

6. The pharmacist documents the interaction with the patient, the agreed management plan, including the medicine management plan and any communication with other healthcare professionals in accordance with legislative, organisational and professional requirements.

This standard always applies to registered pharmacists when dispensing a therapeutic good either directly or indirectly (i.e. no face-to-face contact) to a patient.

Examples of prescribing include:

1. The pharmacist confirms that the prescription or order is legally valid. If the prescription or order is not valid, the pharmacist contacts the prescriber to discuss and resolve the validity of the prescription or order.

2. The pharmacist assesses the information gathered and reviews the prescription or order to determine if dispensing the therapeutic good for the patient is:

AND

3. If the pharmacist has any concerns or determines dispensing the therapeutic good for the patient is not safe or therapeutically appropriate, the pharmacist takes appropriate actions (e.g. implements interim measures, such as defers or limits supply, to facilitate access to the therapeutic good, discusses and resolves issues with the prescriber).

4. The pharmacist creates, or confirms existing is, an accurate and relevant patient healthcare record using an appropriate system (e.g. dispensing software) before dispensing the therapeutic good.

5. The pharmacist accurately dispenses the therapeutic good for the patient according to the prescription or order using an appropriate system (e.g. dispensing software) and quality assurance measures (e.g. barcode scanning, double-checking).

6. The pharmacist labels the medicine container to meet the needs of the patient, and in accordance with legislative, organisational and professional requirements (e.g. Poisons standard, National standard for labelling dispensed medicines, recommended and mandatory cautionary and advisory labels).

7. The pharmacist documents the interaction with the patient (e.g. medicines dispensed, referral, recommendations, off-label use, education) and any communication with the prescriber (e.g. changes to treatment regimen) in accordance with legislative, organisational and professional requirements.

This standard always applies to registered pharmacists when compounding (simple or complex compounding) a medicine for a patient.

Examples of compounding include:

1. The pharmacist completes a risk assessment to determine the appropriateness of the medicine to compound for the patient. This must include:

2. Where a risk is identified, the pharmacist takes appropriate action to mitigate or exclude the risk (e.g. clearly labelling and separating equipment to avoid cross contamination, implementing measures to protect personnel, facilitating access to a suitable alternative commercial medicine that meets the needs of the patient).

3. If the medicine is not appropriate to compound, or the pharmacist does not have the required competencies, equipment or facilities, the pharmacist advises the patient and prescriber, and facilitates access to an alternative product (e.g. contacts prescriber to determine an alternative medicine).

4. The pharmacist implements any necessary safeguards for patient and pharmacist safety (e.g. compounds one medicine at a time, uses personal protective equipment when compounding a hazardous medicine, notifies team members not to interrupt during the compounding process, compounds the medicine when another pharmacist is available to handle other duties).

5. The pharmacist uses appropriate starting materials, compounding practices and techniques to compound the medicine for the patient according to an evidence-based formula (e.g. starting materials produced by a manufacturer with relevant approved licensing and/or certification).

6. The pharmacist uses an appropriate final container and closure and assigns an appropriate expiry date for the compounded medicine (i.e. maintains the physical, chemical and microbiological stability of the medicine and maintains the safety of the stored medicine).

7. The pharmacist labels the compounded medicine container to meet the needs of the patient, and in accordance with legislative, organisational and professional requirements (e.g. Poisons standard, National standard for labelling dispensed medicines, recommended and mandatory cautionary and advisory labels).

8. The pharmacist documents the risk assessment, formula and compounding process each time a medicine is compounded for a patient (e.g. completes a compounding record form, documents the evidence to support the decision to compound the medicine). The formula should be supplied to the patient when requested.

This standard always applies to registered pharmacists who pack medicines.

Examples of packing medicines include:

1. The pharmacist completes a risk assessment to determine the appropriateness of the medicine for packing. This can include:

2. Where a risk is identified, the pharmacist takes appropriate action to mitigate or exclude the risk (e.g. alternative final container, appropriate closure, change formulation).

3. If the medicine is not appropriate to pack, the pharmacist advises the intended recipient of alternative options.

4. The pharmacist packs medicines in accordance with the order or intended use (e.g. imprest order, medication profile for a dose administration aid).

5. The pharmacist packs the medicines to maintain adequate stability and safety (e.g. packing as close as possible to the expected date of use, promptly sealing the container after packing, clean procedures, consider/use child-resistant container).

6. The pharmacist labels the medicine container to meet the needs of the patient, and in accordance with legislative, organisational and professional requirements (e.g. Poisons standard, National standard for labelling dispensed medicines, recommended and mandatory cautionary advisory labels).

7. The pharmacist involved in providing the medicine follows a quality assurance process. This can include checking that:

8. The pharmacist confirms the identity of the person receiving the packed medicine (e.g. using at least three approved identifiers) in accordance with legislative, organisational and professional requirements.

9. The pharmacist checks the packed medicine for appropriateness before providing the medicine (e.g. no signs of deterioration of the packed medicine, no signs of damage to the container that may impact the stability or safety of packed medicines).

10. The pharmacist reviews the appropriateness of the packed medicine at regular intervals (e.g. patient ability to self-administer medicines from the DAA or the medicine bottle with a child-resistant closure, adherence, storage, appropriate quantity). If there is a concern, the pharmacist takes appropriate action to enable safe and effective use of the medicine (e.g. changing administration times of medicines, providing an alternative container, providing aids to help with the removal of the medicine from the container).

11. The pharmacist maintains an accurate and comprehensive record of medicines that are packed. This can include:

This standard always applies to registered pharmacists who directly handle therapeutic goods (e.g. receive, store, distribute, dispose).

Examples of handling of therapeutic goods include:

1. The pharmacist verifies the integrity of therapeutic goods upon receipt from the supplier (e.g. seals intact, no physical damage, maintenance of correct temperature during delivery). If integrity is compromised, the therapeutic good is not used and is returned to the supplier or destroyed.

2. The pharmacist documents the receipt of therapeutic goods from the supplier in accordance with legislative, organisational and professional requirements (e.g. inputs into stock management system, documents date and method of delivery).

3. The pharmacist stores therapeutic goods, including dispensed and unwanted therapeutic goods, in accordance with manufacturers’ directions, and legislative, organisational and professional requirements.

4. The pharmacist appropriately labels therapeutic goods to enable safe storage (e.g. cytotoxic medicines in the dispensary, compounding ingredients in accordance with safety and stability requirements).

5. The pharmacist uses an appropriate system to maintain and monitor the storage conditions of therapeutic goods, in particular temperature-sensitive items (e.g. auditing temperature control equipment, testing of temperature alarms, air handling). If a deviation occurs, the pharmacist completes a risk assessment to determine the integrity of the therapeutic good and takes the appropriate action (e.g. time outside the temperature range and temperature change).

6. The pharmacist completes a risk assessment to determine if therapeutic goods with a greater risk of harm (e.g. diversion risk, hazardous medicine) should be stored in a location that only allows authorised persons to access (e.g. dihydrocodeine formulations in dispensary, hazardous compounding starting materials in a designated area).

7. The pharmacist completes a risk assessment to determine the appropriateness of the therapeutic good for distribution. This can include:

8. Where a risk is identified, the pharmacist takes appropriate action to mitigate or exclude the risk (e.g. suitable transportation container/packaging to maintain cold-chain requirements, postal or delivery record, tamper-resistant packaging).

9. If a therapeutic good is not appropriate to distribute, the pharmacist advises the intended recipient of alternative options.

10. The pharmacist uses an appropriate system to safely dispose of expired and unwanted therapeutic goods, including destroyed medicines (e.g. personal protective equipment for staff involved, crushing of medicines to minimise the risk of diversion, verified medicine disposal service to minimise harm to the environment).

This standard always applies to registered pharmacists who administer or directly supervise the administration of a medicine to a patient.

Examples of administration of a medicine include:

1. The pharmacist completes a risk assessment to determine if the medicine is appropriate for administration to the patient. This can include:

2. Where a risk is identified, the pharmacist takes appropriate action to mitigate or exclude the risk (e.g. implementation of personal protective equipment, alternative formulation or medicine).

3. If the medicine is not appropriate to administer, the pharmacist advises the patient and prescriber, and facilitates access to an alternative medicine (e.g. contacts prescriber to determine an alternative medicine).

4. If administration of the medicine to the patient is outside the pharmacist’s personal competence or scope of practice, the pharmacist refers the patient to an appropriate healthcare professional.

5. The pharmacist explains the medicines and administration process to the patient. This includes the risks, benefits and potential adverse events following administration, the process to report adverse reactions, monitoring, next dose, review and when to consult another healthcare professional or return to the pharmacist.

6. The pharmacist addresses any concerns and expectations raised by the patient (e.g. their health, the medicine management plan, administration process).

7. The pharmacist facilitates patient access to the therapeutic good in accordance with legislative, organisational and professional requirements (e.g. valid prescription for supervised administration of opioid substitution therapy).

8. The pharmacist confirms the correct medicine and dose is selected to administer to the patient.

9. The pharmacist implements safeguards to protect the patient and pharmacist (e.g. administering one medicine to one patient at a time, appropriate personal protective equipment, presence of another adult when administering to a child, notifying team members not to interrupt during the administration process, choosing a time when another team member is available to handle other duties).

10. The pharmacist uses the correct technique to prepare the medicine for administration to the patient (e.g. verified equipment to measure the opioid substitution therapy dose, remove any packaging from a transdermal patch, follow the manufacturer’s directions for reconstitution of a vaccine).

11. The pharmacist prepares the patient to receive the medicine (e.g. identifies the correct site, uses distraction techniques if administering by injection).

12. The pharmacist uses the correct administration technique to administer or supervise the administration of the medicine safely to the patient (e.g. intramuscular administration of influenza vaccine, clean cup and drinking water supplied for administration of methadone syrup).

13. The pharmacist immediately disposes of any clinical waste (e.g. used cups, adhesive strips, sharps, vials) in the appropriate container after administration to the patient.

14. The pharmacist monitors the patient for the required duration after medicine administration to detect any adverse reaction (e.g. 15 minutes after vaccine administration, until consumption of a supervised dose). If an adverse reaction occurs, the pharmacist takes the required steps to minimise harm to the patient.

15. The pharmacist discusses any ongoing care arrangements with the patient and relevant healthcare professionals to maintain continuity of treatment (e.g. ongoing monitoring, follow-up, referral).

16. The pharmacist shares the agreed management plan with the relevant healthcare professionals involved in the care of the patient.

17. The pharmacist updates the patient management plan and any relevant external register with the details of the medicine administered (e.g. dose administration register, Australian Immunisation Register, My Health Record).

18. The pharmacist documents the interaction with the patient (e.g. supply, referral, recommendations, education) and the agreed management plan, including the medication management plan, in accordance with legislative, organisational and professional requirements.

This standard always applies to registered pharmacists when conducting a medication review.

A medication history review that occurs at the time of dispensing a medicine is covered by the actions in Standard 5: Patient assessment and Standard 7: Dispensing.

Examples of a medication review include:

1. The pharmacist compiles a best possible medication history (BPMH) for the patient.

2. The pharmacist reconciles the patient’s medicines using the BPMH. Any discrepancies are discussed and resolved with the prescriber.

3. The pharmacist reviews each medicine in the BPMH for suitability with the patient’s current management plan (e.g. aligns with management plan, safe and appropriate, effectiveness, potential or actual medication-related problems).

4. The pharmacist agrees on the management plan, including the medication management plan, with the patient.

5. The pharmacist addresses any concerns and expectations raised by the patient after the management plan has been discussed (e.g. regarding their health, the medicine management plan).

6. The pharmacist creates a current and accurate patient medication profile.

7. The pharmacist reviews the patient’s medication profile with the aim of medicines optimisation.

8. The pharmacist determines clear, evidence-based recommendations to optimise the safe and quality use of medicines.

9. The pharmacist immediately contacts the relevant healthcare professional if any recommendations require urgent action (e.g. patient is on a contraindicated medicine, pathology results or monitoring required, therapeutic drug monitoring required).

10. The pharmacist works with relevant healthcare professionals to create a clear and current management plan, including a medicine management plan, for the patient.

11. The pharmacist shares the management plan, including the medicine management plan, with other relevant healthcare professionals involved in the care of the patient (e.g. shares a record via secure messaging with other members of the healthcare team).

12. The pharmacist documents the interaction with the patient and the management plan, including the medicine management plan, in accordance with legislative, organisational and professional requirements.

This standard always applies to registered pharmacists when conducting a medicine use evaluation (MUE).

Examples of MUEs include:

1. The pharmacist works collaboratively to identify areas suitable for a medicine use evaluation (i.e. uses the principles of co-design and invites stakeholders to provide information and suggest areas for quality improvement, reviews data to identify areas that may require quality improvement).

2. The pharmacist assesses the identified areas to select a suitable area for the MUE (e.g. relevant to the practice setting, data able to be collected and analysed).

3. The pharmacist collects information to develop or update their knowledge base on the topic (e.g. review and critically appraise relevant literature, review relevant guidelines, engage an expert in the area).

4. The pharmacist defines the evaluation criteria and measures.

5. The pharmacist determines the most appropriate study design (e.g. quantitative, qualitative).

6. The pharmacist identifies and confirms relevant data sources (i.e. confirms suitability with stakeholders).

7. The pharmacist collects data from internal and external sources using a standardised and documented method (e.g. medicine use data, clinical data, national medicine regulatory or safety data, economic data).

8. The pharmacist evaluates the collected data against the pre-determined evaluation criteria and measures.

9. The pharmacist develops clear, non-biased and evidence-based recommendations, supported by the findings, for changes to improve medicines use.

10. The pharmacist discusses the findings and recommendations with stakeholders.

11. The pharmacist appropriately disseminates the findings and recommendations according to the approval level/requirements of the MUE (e.g. publishes the research, provides antimicrobial stewardship data to government).

12. The pharmacist seeks endorsement on the implementation of the recommendations from stakeholders.

13. The pharmacist develops an action plan for the agreed recommendations to be implemented.

14. The pharmacist works with stakeholders to implement the recommendations in the action plan (e.g. delivery of education, update policies and procedures, targeted medication reviews).

15. The pharmacist works with the stakeholders to determine when to evaluate the outcomes of the intervention.

16. The pharmacist discusses the findings of the review with the stakeholders to determine if changes to recommendations are required.

17. The pharmacist works with the stakeholders to determine when to repeat the MUE (e.g. align with new guideline recommendations, dynamic topic may require more frequent evaluations).

18. The pharmacist progressively documents the MUE process during each stage (e.g. stakeholders, data sources, design, evaluation process, findings, recommendations, outcomes).

This standard always applies to registered pharmacists when monitoring patient outcomes and supporting patients to self monitor.

Examples of patient monitoring include:

1. The pharmacist reviews or follows the monitoring requirements outlined in the management plan (e.g. frequency of monitoring required, appropriate digital devices or apps for self monitoring).

2. The pharmacist uses a validated method to obtain objective information from the patient (e.g. glucometer to test blood glucose level, blood pressure monitor to test blood pressure, digital health monitoring aid).

3. The pharmacist discusses the results with the patient (e.g. limitations and significance of the tests in the context of the patient, comparison with reference ranges).

4. The pharmacist addresses any concerns and expectations raised by the patient regarding the results.

5. The pharmacist refers the patient to the relevant healthcare professional when the results are outside the pharmacist’s personal competence or scope of practice.

6. The pharmacist shares the findings with relevant healthcare professionals involved in the care of the patient.

7. The pharmacist documents the interaction with the patient in accordance with legislative, organisational and professional requirements.

This standard always applies to registered pharmacists when providing any medicines and health information either one-on-one with a patient or to a group of people.

Examples of providing medicine and health information one-on-one include:

Examples of providing medicine and health information to a group of people include:

1. The pharmacist collects appropriate and relevant information to develop or update their knowledge base (e.g. journal articles, clinical guidelines).

2. The pharmacist reviews and critically appraises the relevant information.

3. The pharmacist determines the appropriate information to be provided to the patient or member of the healthcare team (e.g. unbiased, evidence-based, accurate, relevant, aligns with public health messaging).

4. The pharmacist provides the appropriate information to the patient or member of the healthcare team in a timeframe that meets their needs. This can include:

5. The pharmacist addresses any concerns and expectations raised by the patient or member of the healthcare team after the information has been provided. The pharmacist refers the patient to the relevant healthcare professional when the concerns and expectations are outside the pharmacist’s personal competence or scope of practice.

6. The pharmacist supports the patient or member of the healthcare team to strengthen their literacy. This may include:

7. The pharmacist confirms with the patient or member of the healthcare team if the information provided meets their needs. If the information does not meet their needs, the pharmacist takes appropriate action to address this.

8. The pharmacist documents the interaction with the patient or member of the healthcare team in accordance with legislative, organisational and professional requirements.

This standard always applies to registered pharmacists when providing a screening, case-finding and risk assessment service to a person.

Examples of screening and risk assessment include:

1. The pharmacist uses a validated tool (e.g. evidence-based, accurate) to obtain objective information from the patient.

2. The pharmacist assesses the information gathered to select the most appropriate method (e.g. point-of-care test, risk assessment tool, screening questionnaire) for the patient (e.g. aligns with identified risk factors, intent of the service, patient preference).

3. The pharmacist discusses with the patient the purpose (e.g. can identify increased risk, help to prevent complications, guide referral for further investigation) and limitations (e.g. not used for diagnosis or changes to existing therapy) of the service.

4. The pharmacist addresses any concerns and expectations raised by the patient (e.g. regarding their health, the method used to assess risk).

5. The pharmacist works with the patient to meet the requirements of the selected method.

6. The pharmacist interprets and evaluates the results in the context of the patient and the potential condition.

7. The pharmacist discusses with the patient:

8. The pharmacist refers the patient, according to the recommendations for the selected method, to the relevant healthcare professional.

9. The pharmacist shares the results with other relevant healthcare professionals involved in the care of the patient.

10. The pharmacist documents the interaction with the patient (e.g. education, results of any tests performed) in accordance with legislative, organisational and professional requirements.

This standard always applies to registered pharmacists when promoting health or delivering a health promotion activity.

Examples of health promotion activities include:

1. The pharmacist identifies topics suitable for a health promotion activity within their scope of practice (i.e. uses co-design principles and invites the community and stakeholders to provide information and suggest topics, aligns with local or national health initiatives and emerging health needs of the public).

2. The pharmacist assesses the identified topics to select a suitable topic (e.g. relevant to the practice setting and community, meets the needs of the community and stakeholders, suitable for delivery by a pharmacist).

3. The pharmacist plans the health promotion activity (e.g. defines the goal, timeline, target audience, cultural considerations, required resources, promotion, follow-up, evaluation).

4. The pharmacist determines what information is appropriate to include in the health promotion activity (e.g. unbiased, evidence-based, accurate, relevant to the intended goal of the activity, public health message resources).

5. The pharmacist determines the most effective way to deliver the health promotion activity (e.g. appropriate mode of delivery, environment, time).

6. The pharmacist translates the appropriate health information into a message or resource suitable for the patient to enable them to actively participate in their own health and wellbeing (e.g. information is in language appropriate for the person, relevant, unbiased, evidence-based).

7. The pharmacist provides information to the patient that can be accessed later (e.g. written information or advice about suitable digital information, such as a leaflet, Self-care fact card or government website).

8. The pharmacist provides information on other upcoming health promotion and health service opportunities to the patient.

9. The pharmacist documents the health promotion activity in accordance with legislative, organisational and professional requirements (e.g. stakeholders, the information provided, process, outcomes)

The terms used in this document and listed below have been sourced and/or adapted from publications listed in the References section.

Term |

Definition |

|

Adherence |

The extent to which a person’s behaviour corresponds with agreed recommendations from a healthcare provider. |

|

Accountability |

Being answerable for one’s actions and the roles and responsibilities inherent in one’s job or position. Accountability cannot be delegated. |

|

Administration of a |

The process of giving a dose of medicine to a person or a person taking or self-administering a medicine. |

|

Adverse (medicine) |

A response to a medicine that is noxious and unintended and occurs at doses normally used or tested in humans for the prophylaxis, diagnosis or therapy of disease, or for the modification of physiological function. |

|

Approved identifiers |

Items of information that can be used to identify a patient when care, medicine, therapy or services are provided. Patient identifiers may include:

|

|

Autonomous prescriber |

Autonomous prescribing occurs when a prescriber undertakes to prescribe within their scope of practice without the approval or supervision of another health professional. The prescriber has been educated and authorised to prescribe autonomously in a specific area of clinical practice. Although the prescriber may prescribe autonomously, they recognise the role of all members of the |

|

Best possible medication history (BPMH) |

A list of all the medicines a patient is using at presentation. The list includes the name, dose, route and frequency of the medicine and is documented on a specific form or in a specific place. All prescribed, over-the-counter, bush and complementary medicines should be included. This history is obtained by a trained healthcare professional interviewing the patient and is confirmed, where appropriate, by using other sources of medicines information (e.g. the patient’s medicines, patient medication list, authorised representative, electronic healthcare record, patient’s general practitioner, recent hospital discharge summary, specialists, community pharmacy dispensing history). |

|

Clinical governance |

An integrated component of corporate governance of healthcare service organisations that ensures everyone is accountable to patients and the community for assuring the delivery of safe, effective and high-quality services. Clinical governance systems provide confidence to the community and the healthcare organisation that systems are in place to deliver safe and high-quality health care. |

|

Co-design and |

An approach to design and development of pharmacy services that actively involves all relevant stakeholders – including patients, pharmacists, managers and other team members. |

|

Collaboration/collaborative care |

A process whereby two or more parties share their expertise and take responsibility for decision-making. For example, through interdisciplinary team-based care. |

|

Complex compounding |

Requires and/or involves special competencies, equipment, processes and/or facilities to manage the higher risks and requirements associated with preparing and dispensing medicines of a complex nature. The Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary and Handbook Compounding Section contains specific examples of complex compounding. |

|

Compounding |

The extemporaneous preparation and supply of a single ‘unit of issue’ of a therapeutic product intended for supply for a specific patient in response to an identified need. A single ‘unit of issue’ should be the quantity that the patient requires for the treatment period determined by the prescriber, and that ensures a quality and efficacious medicine. For the purposes of the Compounding standard, compounding does not include manipulation of a commercial product in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions to produce a ‘ready to administer’ form or repackaging of a non-sterile, non-aqueous commercial product. These two activities do not need to meet the requirements of the Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary and Handbook Compounding Section but still require appropriate procedures, packaging, labelling and expiry date. For further information, refer to the Compounding Section of the Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary and Handbook. |

|

Cultural safety |

A state in which people are enabled and feel they can access health care that suits their needs, are able to challenge personal or institutional racism (when they experience it), establish trust in services, and expect effective, quality care. Cultural safety is determined by the person, families and communities. |

|

Diagnosis |

The identification, by a health professional within their scope of practice, of a condition, disease or injury, made by evaluating the symptoms and signs presented by a patient. |

|

Digital health literacy |

The ability to seek, find, understand and appraise health information from electronic sources and apply the knowledge gained to addressing or solving a health problem. |

|

Dispensing |

The safe provision of a medicine to a patient, which involves reviewing an order for a medicine (e.g. prescription, medication chart, patient request) in the context of the patient’s medical history, and the preparation, packaging, labelling, documentation and transfer of the prescribed medicine. It includes providing advice to the patient. |

|

Dose administration aid (DAA) |

A tamper-evident, well-sealed device or packaging system that allows organisation of doses of medicine according to the time of administration. |

|

Electronic health (eHealth) record |

A person’s health information stored in a secure digital system that allows authorised healthcare providers to access up-to-date information to improve care coordination and can reduce the risk of medical errors. |

|

Embedded pharmacist |

A pharmacist who is fully integrated within the care team and wherever medicines are used – including within primary care, residential care and other settings where medicines are prescribed, supplied and administered to patients. |

|

Equitable health care |

Health care that meets every person’s health needs, irrespective of age, gender, ethnicity, sexuality, ability or other factors. |

|

Evidence-based practice |

A process that integrates the best available scientific evidence with professional judgement and patient preferences to make clinical decisions. |

|

Hazardous substance |

Substances, mixtures and articles that can pose a health or physical hazard to humans. |

|

Health care |

The prevention, treatment and management of illness and injury, and the preservation of mental and physical wellbeing through the services offered by healthcare professionals, such as medical, nursing, and pharmacy. |

|

Healhcare |

A healthcare provider trained as a health professional. Healthcare professionals may provide care within a health service organisation as an employee, a contractor or a credentialed healthcare provider, or under other working arrangements. They include pharmacists, nurses, midwives, medical practitioners, allied health practitioners, technicians, scientists and other healthcare professionals who provide health care, and students who provide health care under supervision. |

|

Health literacy |

Health literacy can be separated into individual health literacy and the health literacy environment. Individual health literacy is a person’s skills, knowledge, motivation and capacity to access, understand, appraise and apply information to make effective decisions about health and health care and take appropriate action. The health literacy environment is the infrastructure, policies, processes, materials, people and relationships that make up the healthcare system, that affect how people access, understand, appraise and apply health-related information and services. |

|

Health promotion |

Focuses on preventive health and encompasses a combination of interventions to enable individuals and communities to increase awareness, have control over and improve their health. This occurs with community participation through attitudinal, behavioural, social and environmental changes. |

|

Incident |

An event or circumstance where an error has been made, and a person or patient becomes aware of the error, irrespective of any outcome. This could include a dispensing error, an error with advice or a professional service. |

|

Informed consent |

Permission granted voluntarily by a patient or person who has been adequately informed (e.g. of options, risks, benefits) and has the capacity to understand, provide and communicate their permission. Consent can be verbal, written or implied (e.g. patient providing a prescription to the pharmacist, patient holding their arm out to have their blood pressure taken). |

|

Interdisciplinary care |

An approach to care that involves team members from different disciplines working collaboratively, with a common purpose, to set goals, make decisions and share resources and responsibilities. A team of healthcare professionals from different disciplines, together with the patient, undertakes assessment, diagnosis, intervention, goal-setting and the creation of a care plan. The patient, their family and carers are involved in any discussions about their condition, prognosis and care plan. |

|

Leadership |

The application of skills and attributes needed to inspire, motivate and lead a healthcare team and lead processes that improve the delivery of safe and high-quality health care. |

|

Management plan |

A plan of systematic care outlined for the patient, reflecting shared decisions made with patients, families, carers and other support people about tests, interventions, treatments and other activities needed to achieve the goals of care provided by the pharmacist in collaboration with the patient and other healthcare professionals. For the purposes of these standards, the management plan includes diagnosis, recommendations for pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, duration of intervention, monitoring, therapeutic goals, education and advice provided, required follow-ups to monitor the patient’s progress and when to refer to other healthcare professionals or return to the pharmacist. |

|

Medical device |

Medical devices are therapeutic goods that can be used to diagnose, prevent, treat and monitor medical conditions. They include surgical equipment, syringes, gloves, pacemakers, baby incubators and implants. |

|

Medical history |

Details of a person’s current and past medical and social history and cultural and demographic characteristics. |

|

Medication review |

A systematic, comprehensive and collaborative assessment of medication management for an individual person that aims to optimise the patient’s medicines and outcomes of therapy by providing a recommendation or making a change. |

|

Medication profile |

A comprehensive summary of all regular medicines taken or used by a person. It is intended to promote better understanding and management of medicines by people, as well as improve communication between people and their healthcare providers. |

|

Medicine |

A substance used to treat or prevent disease and to maintain well-being. It can include prescription, over-the-counter, compounded, complementary and alternative or bush medicine. |

|

Medicines history |

History of current and previous medicines, alcohol and substance use (including illicit substances), previous adverse drug reactions, allergies, medicines and treatments that have been modified or stopped recently and an indication of how the person takes or uses their medicines. |

|

Medicines or medication literacy |

The degree to which people can obtain, comprehend, communicate, calculate and process specific information about their medicines to make informed medicines and health-related decisions to safely and effectively use their medicines, regardless of the mode by which the content is delivered (e.g. written, oral or visual). |

|

Medicine management plan |

A continuing plan for the use of medicines that arises from a medication management assessment and is developed by the healthcare professional in collaboration with the patient. |

|

Medicine use evaluation |

A structured quality improvement activity to assess medicine use with the goal of optimising the quality, safety and cost-effectiveness of medicine use. |

|

Monitoring |

Regular measurement and assessment of specific clinical and social parameters to assist patients undergoing treatment for, or at risk of, specific health conditions. |

|

Monitoring plan |

A continuing plan for the regular monitoring of specific parameters developed in collaboration with the patient. |

|

My Health Record |

An online summary of a person’s key health information, controlled by the person and managed by the Australian Digital Health Agency. |

|

Near miss |

An event that could have resulted in unwanted consequences, but did not because either by chance or through timely intervention the event did not reach the patient (e.g. an error is made in the dispensing of a medicine, but the error has been identified and corrected before the medicine reaches the patient, and the patient is unaware of the event). |

|

Opioid substitution therapy (OST) |

Different terminology is used by jurisdictions to refer to OST including opioid dependence treatment (ODT), opioid maintenance treatment (OMT), opioid replacement therapy (ORT) and medication-assisted treatment of opioid dependence (MATOD). |

|

Patient |

A person who is receiving care in a healthcare service organisation. ‘Patient’ also extends to the person’s support network, which can include authorised representatives, carers (including kinship carers), families, support workers and groups or communities. For the purposes of these standards, a patient can be a human, an animal or a group of one species of animal. When it is an animal or group of animals, the owner of the animal/s is referred to. |

|

Patient- or |

Person-centred care involves understanding the person’s values, needs, attitudes and preferences to enable mutual respect and shared decision-making. An approach to the planning, delivery and evaluation of health care that is founded on mutually beneficial partnerships among healthcare professionals and patients. Person-centred care is respectful of and responsive to the preferences, needs and values of patients and people. Key dimensions of person-centred care include respect, emotional support, physical comfort, information and communication, continuity and transition, care coordination, involvement of family and carers, and access to care. |

|

Patient healthcare record |

Information held about a patient in paper form or electronic form, which may include:

|

|

Personal competence |

A time-sensitive, dynamic aspect of an individual pharmacist’s ability to accurately and safely complete a task (i.e. training and knowledge needs to be up to date). |

|

Personal protective equipment |

Equipment used to prevent and control infection, including appropriate gloves, waterproof gowns, goggles, face shields, masks and footwear. |

|

Pharmacist |

A person registered under the National Law (the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law, as in force in each state and territory) to practise in the pharmacy profession, other than as a student; or who holds non-practising registration in the pharmacy profession under the National Law. In these standards, ‘pharmacist’ refers to the registered pharmacist and, where applicable, the team that a pharmacist may manage or have oversight/responsibility for. The actions contained in the standards are expected to apply to all team members involved in providing the service. |

|

Prescriber |

A health professional authorised to undertake prescribing within the scope of their practice. |

|

Prescribing |

An iterative process involving the steps of information gathering, clinical decision-making, communication and evaluation that results in the initiation, continuation or cessation of a medicine. The definition of prescribing used may differ from the definition of prescribing provided in the legislation governing the use of medicines in each jurisdiction. Health professionals are advised to review the legislation in effect in the state or territory in which they practise to ensure they understand their legal authorisation to prescribe medicines. |

|

Public health |

The science and art of promoting health, preventing disease, and prolonging life through the organised efforts of society. |

|

Quality improvement |

The combined efforts of the workforce and others—including people, patients and their families, researchers, planners and educators – to make changes that will lead to better patient outcomes (health), better system performance (care) and better professional development. Quality improvement activities may be undertaken in sequence, intermittently or on a continuous basis. |

|

Responsibility |

To be entrusted with or assigned a duty or charge. In many instances, responsibility is assumed, appropriate to one’s duties. Responsibility can be delegated as long as it is delegated to someone who has the ability to carry out the task or function. The person who delegated the responsibility remains accountable, along with the person accepting the task or function. Responsibility is about accepting the tasks/functions inherent in one’s role. |

|

Risk assessment |

Assessment, analysis and management of risks. It involves recognising which events may lead to harm in the future and minimising their likelihood and consequences. For the purposes of these standards, a risk assessment may be a formal process involving documentation and maintenance of written records, or it may be an informal process. |

|

Scope of practice |

A time-sensitive, dynamic aspect of practice that indicates those professional activities that a pharmacist is educated, competent and authorised to perform and for which they are accountable. |

|

Screening and risk assessment |

A systematic process used to identify members of a defined population who may be at risk of a disease or may have undiagnosed disease, evaluate that risk and provide advice or referral as appropriate. |

|

Shared decision-making |

A consultation process in which a healthcare professional and a patient jointly participate in making a health decision, having discussed the options and their potential benefits and harms and having considered the patient’s values, preferences and circumstances. |

|

Simple compounding |

Compounding performed by any registered pharmacist that involves compounding non-sterile, non-hazardous medicines using a formula published in a recognised and reputable reference (e.g. Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary and Handbook) or using another formula where reliable information confirming quality, stability, safety, efficacy and rationality is available. Simple compounding excludes any compounding that meets the definition of complex compounding. The Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary and Handbook Compounding Section contains specific examples of simple compounding. |

|

Standard operating procedure |

A written document with a set or sequence of instructions for a routine or repetitive activity. It assists in delivering a service or activity to a consistent standard and outcome. |

|

Structured prescribing arrangement prescriber |

Structured prescribing occurs when a prescriber with a limited authorisation to prescribe medicines by legislation, requirements of the National Board and policies of the jurisdiction or health service prescribes medicines under a guideline, protocol or standing order. A structured prescribing arrangement should be documented sufficiently to describe the responsibilities of the prescriber(s) involved and the communication that occurs between team members and the person taking medicine. Health professionals may work within more than one model of prescribing in their clinical practice. |

|

Supervised prescriber |

Supervised prescribing occurs when a prescriber undertakes prescribing within their scope of practice under the supervision of another authorised health professional. The supervised prescriber has been educated to prescribe and has a limited authorisation to prescribe medicines that is determined by legislation, requirements of the National Board and policies of the jurisdiction, employer or health service. The prescriber and supervisor recognise their role in their healthcare team and ensure appropriate communication occurs between team members and the person taking medicine. |

|

Therapeutic good |

Therapeutic goods are broadly defined as products for use in humans in connection with preventing, diagnosing, curing or alleviating a disease, ailment, defect or injury; influencing, inhibiting or modifying a physiological process; testing the susceptibility of people to a disease or ailment; influencing, controlling or preventing conception; or testing for pregnancy. This includes items used as an ingredient or component in the manufacture of therapeutic goods, or used to replace or modify parts of the anatomy. In these standards, this term is used to refer to a medicine, ingredient for compounding or medical device for use in humans or animals. |

The development of the Professional Practice Standards, Version 6, is supported by funding from the Australian Government under the Seventh Community Pharmacy Agreement.

The work to develop the standards included review by experts, open and targeted stakeholder consultation and the consensus of organisations and individuals involved.

The Pharmaceutical Society of Australia (PSA) thanks all those involved in the process and gratefully acknowledges the contribution of the following individuals and organisations.

Dr Deanna Mill, Chair

Ilnaz Roomiani, Department of Health

Dr Phi Le, Department of Health

Jerome Boland, Department of Health

Mark Kirschbaum, Pharmacy Board of Australia

Dr Josephine Maundu, Australian Pharmacy Council

Jessica Seeto, The Pharmacy Guild of Australia

Mike Stephens, National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation

Dr Jacinta Johnson, The Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia

Flynn Swift, National Australian Pharmacy Students’ Association

Gary West, Pharmaceutical Defence Limited

Timothy Plunkett, Australian Digital Health Agency

Professor Debra Rowett, Council of Pharmacy Schools

Janelle Dockray, Professional Pharmacists Australia

Debra Letica, Consumers Health Forum of Australia Professor

Lisa Nissen, academic.

Hannah Knowles, Chair Anne Todd, Chair Andrew Sluggett, Chair

Hannah Mann, Craig Stevens, Nerida Croker, Michelle Hansen, Dee-Anne Hull, Michael Cousins, Ayomide Ogundipe, Lisa Wark, Dr Lynda Cardiff, Elise Wheadon, Rachel Rees, Brenda Shum, Dr Manya Angley, Deborah Hurwitz, Dr Kirsty Galbraith, Dr Richard Brightwell Janelle Dockray, Dr Selena Boyd, Suzanna Valastro, Michael Bakker, Branko Radojkovic, Dr Beverley Glass, Kerry-Anne Casanova, Karla Wright, Margaret Fagan, Mina Naguib.

Jacob Warner, Peter Guthrey, Claire Antrobus, Kay Sorimachi, Chris Campbell, Emma Abate, Nena Nikolic, Ness Clancy, Madeline Thompson, Carolyn Allen, Leah Robinson, Natalie Bedini, Marwa El Jamaly, Marwa El Jamaly and Haider Ordonez.

This publication contains material that has been provided by the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia (PSA), and may contain material provided by the Commonwealth and third parties. Copyright in material provided by the Commonwealth or third parties belong to them. PSA owns the copyright in the publication as a whole and all material in the publication that has been developed by PSA. In relation to PSA owned material, no part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), or the written permission of PSA. Requests and inquiries regarding permission to use PSA material should be addressed to: Pharmaceutical Society of Australia, PO Box 9464, Deakin ACT 2600.Where you would like to use material that has been provided by the Commonwealth or third parties, contact them directly.

Neither the PSA, nor any person associated with the preparation of this document, accepts liability for any loss which a user of this document may suffer as a result of reliance on the document and, in particular, for:

Notification of any inaccuracy or ambiguity found in this document should be made without delay in order that the issue may be investigated and appropriate action taken.

Please forward your notification to: Pharmaceutical Society of Australia, PO Box 9464, Deakin, ACT 2600.

Images in the standards were produced in line with COVID-19 restrictions at the time they were taken.

Date of Publication: July 2023

© Pharmaceutical Society of Australia Ltd, 2023